Sea Mills: The beginning

The Sea Mills we know today can be seen as an area formed by politics and war in an era of huge change.

On 24th November 1918, two weeks after the end of WW1 Lloyd George, Prime Minister of the Liberal / Conservative coalition government that had seen Britain through the war made a speech in Wolverhampton promising to make Britain “a country fit for heroes to live in” (1). The election that followed soon afterwards was the first held since the Representation of the People Act 1918. It was the first where all men over the age of 21 and all women over 30, if they or their husbands were owners of property could have their say by voting. It was also the first election where women could stand as candidates and where everyone cast their vote on a single day – although the actual count was delayed so that the votes of troops still serving overseas could be counted (2). The coalition government won by a landslide.

The poor health of many men conscripted during WW1 had highlighted the role poor housing played in the health of the nation (3). Those who had survived the horrors of the trenches returned home expecting the world to be a better place. There had been dock strikes and more. “Lawlessness at Liverpool. Troops fire over pillaging crowds.. warships despatched : Tanks Arrive” declared the Manchester Guardian on Monday August 4th (4). The Government feared national civil unrest and even revolution as there had been in Russia if conditions for the working classes did not improve (5).

Improvement of housing for the working classes became a key aim of the government’s policy. Dr Christopher Addison the President of the Local Government Board, soon to become the first Minister for Health was tasked with making this happen.

Addison comes across as a visionary, a medical doctor who had entered politics with the intention of improving the health of the poor. He had been key in the passing of the 1911 National Insurance Bill, which provided the first contributory insurance scheme for wage earners against illness and unemployment. It was the beginning of the modern welfare state. He clearly understood the effect of housing conditions on health and well being. He was responsible for the Housing and Town Planning Act 1919 (known as the Addison Act) which allowed local authorities to build large scale council estates.

In 1919 there was a large shortage of quality housing. Many houses were needed within a short period of time to house returning soldiers and their families and for slum clearance. Because of the war little building had been competed for years. There was a backlog of projects and a shortage of materials and skilled labour. Prior to 1919 private enterprise had been responsible for 95% of all housing provision (6). Building houses was expensive and the Rents and Mortgages Restriction capped the amount landlords could charge (7). It was unlikely that the private sector was going to be able to provide houses cheaply enough to solve the problem, rents would simply not be affordable for ordinary working people.

The Addison Act gave local authorities the task of building the required homes, with the state assisting with the funding over that raised by a penny on the rates. In many cases this amounted to central government taking on 90% of the cost of building. However it was up to councils to fund the land cost. Many issued housing bonds, usually at an interest rate of 6% for local people to buy (8). It was under the Addison Act that building began in Sea Mills.

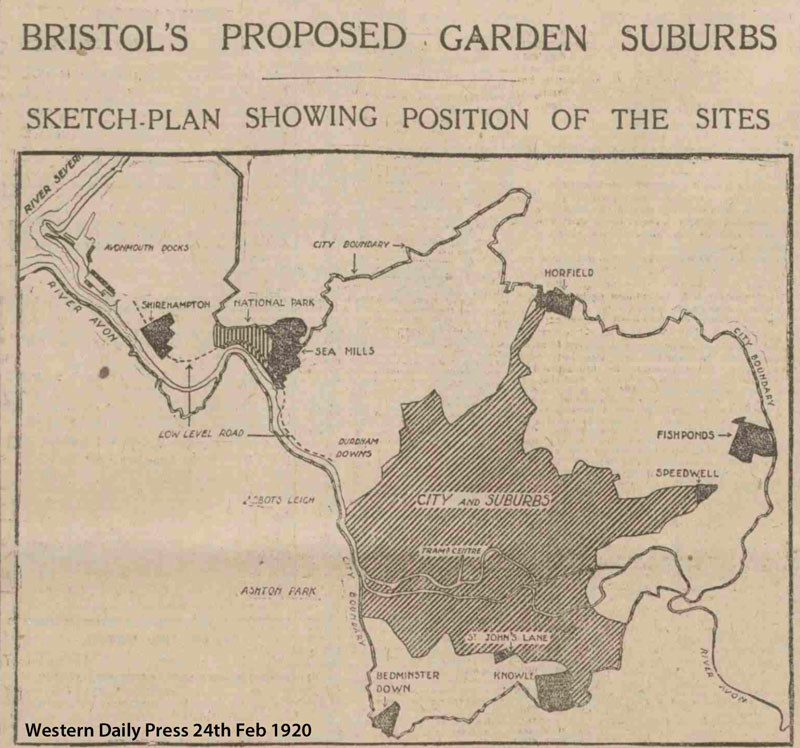

Sea Mills is one of several housing schemes proposed at the same time in Bristol – Hillfields (Fishponds), Knowle, Horfield, Speedwell and St John’s Lane (9). There was also a site at Shirehampton, where Army Huts from the Remount Camp where converted into temporary accommodation (10). The building of a low level road between Bristol and Avonmonth, The Portway, was also part of the proposal. Of the inter-war council estates built in Bristol, Sea Mills is the best example of a garden suburb, built on garden city principles. Garden cities or suburbs feature pleasing symmetrical layouts, well designed and light, spacious, housing at low densities, interspaced with green spaces and with their own amenities. The garden city idea had been around for a while, favoured by Ebenezer Howard (Garden Cities of Tomorrow 1902) and Raymond Unwin (Nothing Gained by Overcrowding 1912). There had been previous attempts to build Garden Suburbs in Bristol at Avonmouth and Shirehampton by Philip Napier Miles and involving local names such as Sir George Oatley and F.N Cowlin (11) all of whom ultimately contributed in their various ways to Sea Mills Garden Suburb.

The Tudor Walters Committee of which Raymond Unwin was also a member was asked to report on the condition of housing in 1918. Its findings were influenced by Garden City principles and laid down the high standards for the council housing which would be built.

The report recommended that houses should contain a minimum of three rooms downstairs – living room, parlour and scullery. Upstairs there were to be three bedrooms with two of them big enough to contain two beds. A Larder and a bathroom were considered essential (12). Housing was to be built in short terraces at a density of 12 per acre, to allow the penetration of sunlight even in winter. These were the standard to which the first houses in Sea Mills were built.

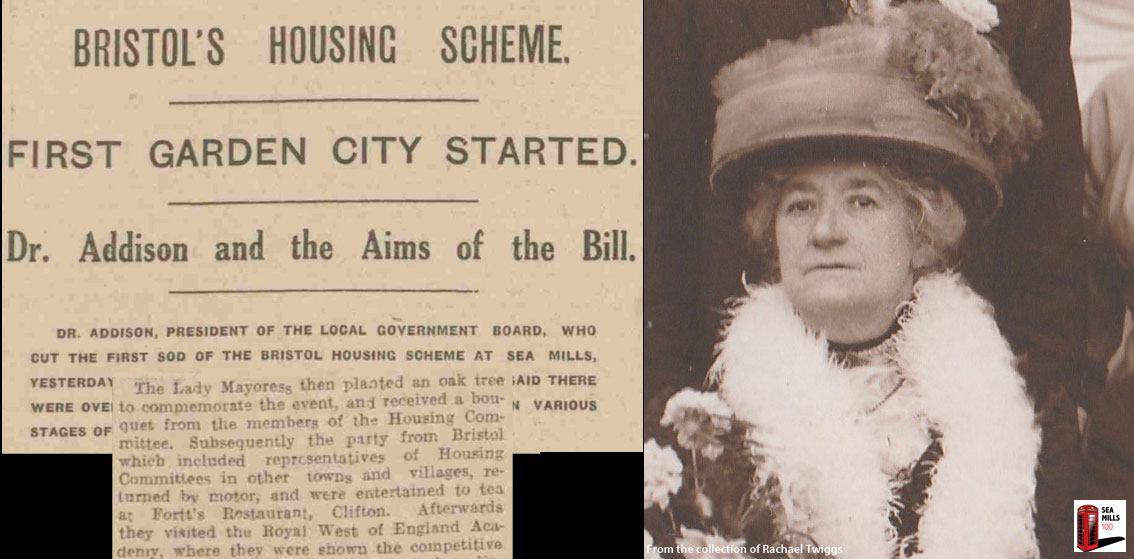

On 4th June 1919 Christopher Addison visited Hillfields and Sea Mills. In Hillfields he watched some drainage being installed. While at Sea Mills he gave a short speech and the Lady Mayoress – Mrs Emily Twiggs ceremonially planted an oak tree which is still known as Addison’s Oak today.

Addison later spoke at the Colston Hall, reported in the local press, “Another important provision in the new scheme was to secure that we had our houses in future not built in dismal rows (applause) without a patch of green or a bit of ground about them. He hoped that the great housing undertaking would be marked in coming generations as one which at least covered our country with pleasant well-planned living houses (applause). Until we had got our houses with air about them, with people not driven like rats underground and crowded on top of each other, so long should we have to spend masses of money every year on avoidable sickness (applause). Well-planned housing schemes were just as essential to the interests of the peoples health and well- being as to their social comfort and to the amenities of ordinary life” (13).

By April 1920 with demobilisation from the army in its last stages and 4 million men having been brought back from fighting forces (14) pressure on housing must have been high. In July Mr Savory – Chair of the Housing and Town Planning Committee made an appeal to the people of Bristol, calling on their patriotism and asking them to buy 6% bonds to “help forward this great movement for the betterment and regeneration of our beloved city…We all know that the solution to the housing problem, by which all our fellow citizens of the working classes will eventually be re-housed under healthful and sanitary conditions, giving opportunity for the reasonable enjoyment of life, will do more for their welfare and happiness and the settlement of industrial unrest than all other schemes put together.” Some of the new houses in the city had already been let, he said, “and the tenants express themselves in terms of deepest thankfulness for the altered conditions in which they are now living” (15).

It was not simple though. The cost of building was grossly out of proportion with the rents that could be charged. With a cost of £1200 for a parlour house, including the land (16) the true economic rent was estimated at 40-50 shillings a week (17) while tenants were in reality paying only twelve. Shortage of labour was also making building difficult, slowing progress and putting up costs (17). Labour and materials shortages had somewhat resolved themselves by 1921 but even so, the cash strapped coalition government abandoned the subsidies. Fortunately for Sea Mills and for working people up and down the country subsidies (albeit less generous ones) were reintroduced under the 1923 and 1924 Housing Acts (8).

The first houses to be completed in Sea Mills were the Dorlonco houses in Sylvan Way. Their innovative design, using concrete allowed them to be completed even though bricks and brick laying skills were in short supply. In July 1920 the Western Daily Press described the completed houses as having “quite a seaside appearance” and said “they appear to possess every quality to make a really comfortable home” (10). By October 1920 16 new houses had been let in Sea Mills (then known as Sea Mills Park), with preference given to ex-servicemen with families. One on the corner of Sylvan Way and Shirehampton Road was let to the very first tenants on the estate, Alfred Burchell and his family. We have not discovered if Burchell was a WW1 veteran but he was to become a founding member and the first church warden of St Edyth’s Church, a valued member of the community. As families moved in it was noted that “There was a noticeable increase in the health of the children, and many of the housewives said they had never lived in houses so full of convenience and in which comfort had been so well studied.” (16)

While the houses were well equipped, other facilities for the new suburb took a while to arrive. Shops, churches, a library, a school and community centre all came later. All were campaigned for by local residents and in the case of the community centre built with their own hands. The community were active in organising activities for themselves, the Sea Mills flower show was soon a regular event and the Sea Mills Park football club played on the Recreation Ground (The Rec) from early days. The football team still exists and remains the only reminder of the original name.

Mary Milton (c) 2020

(1) Campbell Gosling, George Lloyd George’s Ministry Men. Available from: http://ww1centenary.oucs.ox.ac.uk/?p=3518) [Accessed 21 May 2020]

(2) Craig, F.W.S. (1989), British Electoral Facts: 1832–1987, Dartmouth: Gower, cited at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/1918_United_Kingdom_general_election

(3) Powell, Adam (2019) Soldiering On: British Tommies After the First World War. Cheltenham: History Press

(4) The Guardian (1919) London, Greater London, England · Mon, Aug 4, 1919 · Page 7 https://www.newspapers.com/image/258406689 [Accessed on 14 May 2020]

(5) Webb, Simon (2016) 1919: Britain’s Year of Revolution. Pen and Sword History

(6) Kirby, David A (1971) The inter-war council dwelling: a study of obsolescence and decay. Tho Planning Review, 42(3), pp 250-268

(7) Yorke, Frank (2017) Homes Fit for Heroes The Aftermath of the First World War. Berkshire: Countryside Books

(8) Sitwell, Martin Housing the returning soldiers “Homes Fit For Soldiers” www.socialhousing history.uk/wp/index.php/homes-fit-for-heroes

(9) Western Daily Press (1920) Bristol’s Proposed Garden Suburbs. Feb 24th 1920

(10) Western Daily Press (1920) Concrete Dwellings at Sea Mills. 16th Jul 1920 p 5 col 2

(11) Roberts, John (2007) the Definition and Characteristics of a Post-WW1 Garden Suburb with particular reference to Sea Mills Garden Suburb, Bristol. Bristol: Save Sea Mills Garden Suburb & Sea Mills and Coombe Dingle Community Project

(12) Barnes, Harry (1934). The Slum: Its story and Solution. Cited at https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tudor_Walters_Report [accessed 21 May 2020]

(13) Bristol Times and Mirror (1919) Dr Addison Cuts First Sod at Sea Mills. 5th June 1919

(14) Clifton and Redland free press (1920) Resettlement Notes. Apr 22 1920 p 3 col 4

(15) Western Daily Press (1920) Housing Bonds Week. 16 Jul 1920 p 5 col 2

(16) Western Daily Press (1920) St James’s Mr H J Cridland on Housing. 16th Oct 1920 p 3 col 3

(17) Western Daily Press (1920) Stupid Fetish. 16 July 1920 p 5 col 5